Social determinants of health are factors that affect our health, wellbeing, and everyday quality of life. These aspects also contribute to caregiver burden, leading to lower health for carers and care recipients. Unfortunately, many family caregivers lack the support and resources to overcome these barriers. This article explores how the role of caregiving impacts informal caregivers and ways that health systems and experts can address the problem.

Updated March 1, 2023

What Is Caregiver Burden?

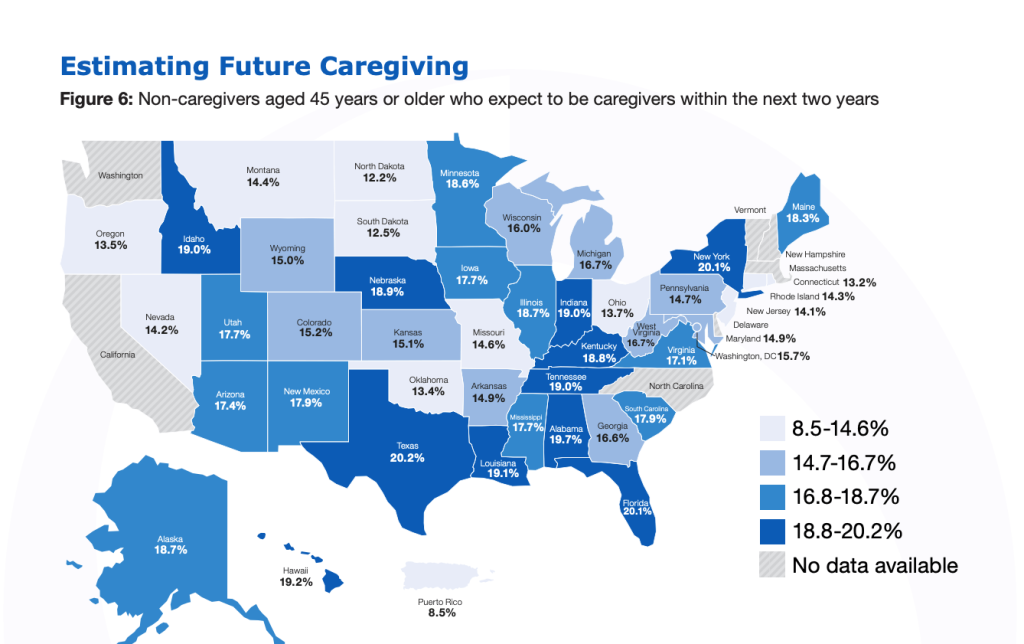

Chances are, you either know someone who is a family caregiver, or you provide care for a loved one. It’s not surprising, given that family caregivers are one of the fastest-growing groups in the US.

According to Caregiving in the US 2020 by the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and AARP, family members who provided care for a loved one rose by 9.5 million from 2015 to 2020. In other words, more than one in five Americans volunteer their unpaid time and resources to support a loved one.

Informal caregivers, which include family members and friends, are an overlooked yet invaluable resource in healthcare. In many cases, they are the ones who are chiefly responsible for managing their loved one’s health. In addition, because family caregivers are the most trusted and familiar members of their loved one’s care team, they are vital liaisons between the care recipient and the rest of the care team.

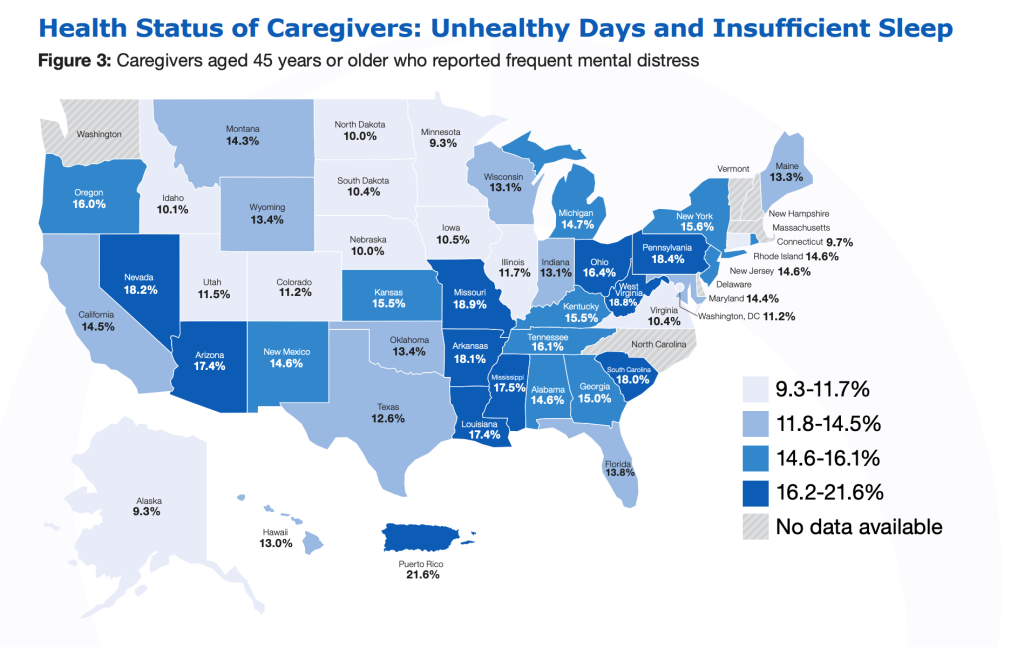

Studies show that caregiving can significantly affect mental, physical, emotional, and financial health. This negative impact, known as caregiver burden, is a serious problem affecting millions daily. For example, the 2020 Caregiving in the US report found that family caregivers report lower health than five years ago. Furthermore, report researchers found:

- 85% of “sandwich generation” caregivers (adults who care for their parents and children) experience poor mental health.

- 20% report moderate to extreme financial strain.

- 11% experience worse physical health because of their role as caregivers.

Resilience can help minimize these adverse consequences and lower the risk of caregiver burden. Caregivers with higher resiliency can also better care for their loved ones. Yet, despite the benefits family caregivers offer their loved ones and the healthcare ecosystem, many lack the resources to build resilience against the daily stressors of their role.

What Are Social Determinants Of Health?

Social determinants of health can exasperate family caregiver burden further. Social determinants of health are factors that influence our health and quality of life and include access to necessities such as:

- Nutritious food

- Equitable healthcare

- Safe and affordable housing

- Affordable and reliable transportation

- Employment and education opportunities.

Social determinants of health, such as access to food and shelter, can affect overall health by as much as 80%. Awareness and education of social determinants of health and their effect on family caregivers have large-scale benefits beyond individual families.

For example, clinicians aware of common barriers facing caregivers can guide them to the right resources. They can also influence policy proposals (workplace benefits for caregivers, respite care options, community supports, etc.) to enhance patients’ quality of life.

Caregiver Burden Disproportionately Affects Underrepresented Groups

Historically, social determinants of health have disproportionately affected Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. Health inequalities arising from these communities’ unmet needs can also apply to caregiving, as family caregivers often face similar challenges due to their societal position.

For example, compared to Whites, Black adults 65 and older are 30% more likely to become informal or professional caregivers. Similarly, Latinos are more likely to become family caregivers. However, these groups often lack access to community or financial resources to support them, further contributing to poorer health and higher rates of caregiver burden.

Caregiver Burden Driven By Unmet Health Needs

Health, caregiving, and socioeconomic factors are intrinsically connected and significantly affect the ability to provide care. Unfortunately, this relationship can make it difficult for caregivers to find help to address their problems. For example:

- A caregiver who works full-time and experiences chronic fatigue may be more likely to make a mistake, such as forgetting their loved one’s appointment.

- Someone suffering from chronic pain because they can’t afford treatment may struggle to help their loved one out of bed, bathe, and do other tasks.

Caregiving is a similar social condition that affects the individual’s health. In a 2022 article, Kathleen Stillo, General Manager and Chief Care Delivery Officer at Commonwealth Care Alliance, noted, “The role of caregiver has such a profound impact on health it should be considered a diagnosable condition.” For example,

- Rates of depression and anxiety are six times higher in female caregivers than in non-caregivers.

- The risk of heart disease, cancer, arthritis, and other chronic diseases is twice as high for caregivers as for non-caregivers.

- High levels of emotional and mental stress increase the risk of death by more than 60% for caregivers than non-caregivers.

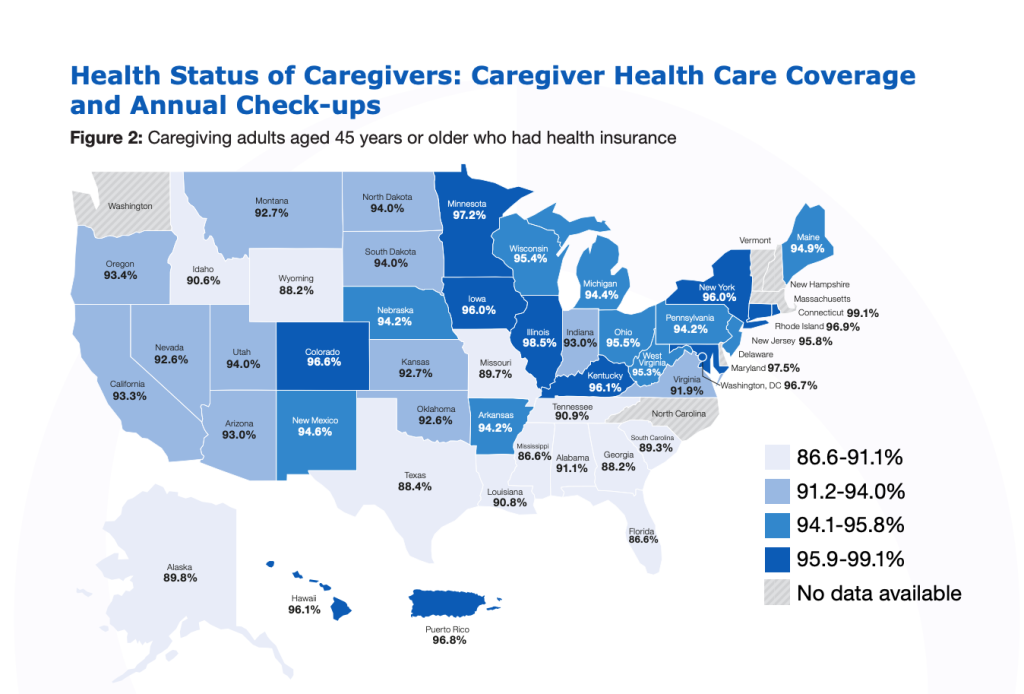

Caregiving’s toll – and consequently, caregiver burden – is unmistakable. But without the support of loved ones, even informal, many seniors would not receive the help they need to remain at home. This is particularly true for roughly 30% of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. In addition, according to a 2020 research brief by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), multiple chronic conditions affected nearly 77% of dual Medicare and Medicaid recipients, which consist of low-income seniors and people with disabilities.

Dual-eligibles with one or more health issues typically have more intensive care needs and higher health costs. As a result, family members or friends who care for someone in this group may face even more complexities in their role, further straining their health and finances and reporting higher rates of caregiver burden.

Caregiver Burden Driven By Unmet Economic Needs

In addition to the physical consequences of caregiver burden, several studies show that caregiving often places financial strain on the individuals who adopt the role. Spouses, those with a high level of responsibility, primary caregivers, and long-distance caregivers are particularly susceptible to financial strain. This is likely due to the numerous hours of care and supervision required and the cost of professional support.

AARP and NAC’s Caregiving in the US 2020 report exemplified financial strain as:

- Accumulating more debt

- Being unable to save money

- Depending on short-term savings

- Borrowing money from friends and family

- Struggling to afford basic needs such as food

- Paying bills late or being unable to pay them at all

- Depleting long-term savings to afford other things.

The approximate value of unpaid caregiving was $470 billion in 2019. Furthermore, a 2016 article published in the National Academies Press noted that family caregivers often incur substantial financial setbacks “with respect to both direct out-of-pocket costs and long-term economic and retirement security.”

This is especially true for working caregivers, who may struggle to save for their future or receive fewer employer-provided retirement benefits due to disruptions caused by caregiving duties. In 2020, 61% of caregivers worked, with 60% working full-time. Likewise, the average working caregiver worked 35.7 hours each week and provided an average of 24 hours of care each week. So naturally, this burden leads to lower performance in both areas.

However, given the critical nature of their role, caregivers must often prioritize their caregiving duties over work for their loved one’s sake. 61% of caregivers reported that their role affected their employment situation in one or more ways. For example, according to AARP and NAC:

- 53% arrived to work late, left early, or took time off work to provide care

- 15% reduced their hours

- 14% took a leave of absence

- 8% received a warning about performance or attendance

Family caregivers often lack access to resources that can help minimize disruptions at work (thereby reducing their risk of caregiver burden). Unfortunately, few employers offer protections or benefits for working caregivers. According to a 2021 report from Blue Cross Blue Shield, the “direct economic effect resulting from caregiving is estimated at nearly $44 billion through the loss of 656,000 jobs and an additional 791,000 caregivers suffering from absenteeism issues at work.”

Ultimately, the financial consequences of caregiving can restrict caregivers’ ability to live in safe communities, access nutritious food, seek treatment for their health, and more. Even for those who don’t experience an immediate financial impact, loss of income could prevent caregivers from saving as much for retirement and their future care needs.

Caregiver Burden Driven By Food Insecurity

The economic impact of caregiving can also drive food insecurity and poor nutrition, further contributing to caregiver burden and lower health. For example, a 2015 report found that caregivers were “significantly more likely than non-caregivers to experience household-level food insecurity, individual-level hunger, or both.”

Concerningly, the rate of family caregivers who experience food insecurity is rising. In addition to aggravating other health issues that arise from caregiver stress, food insecurity contributes to numerous health problems, such as:

- Inflammation

- Chronic conditions

- Reduced management of chronic diseases like diabetes

Poor nutrition in informal caregivers can negatively impact care recipients by restricting the caregivers’ ability to provide care over time. This problem can significantly lower both parties’ wellbeing and lead to higher healthcare costs. For this reason, addressing food insecurity and its risks is an urgent matter of public health.

Addressing Social Determinants Of Health That Drive Caregiver Burden

Helping informal caregivers overcome social determinants of health won’t only benefit the individuals and their families. In addition, a robust population of more resilient caregivers offers advantages for society.

For example, care provided by family members could, in some cases, replace the need for traditional healthcare services. This reduces the utilization of medical services and facility care, lowering costs for Medicare and Medicaid. Insurers can also lower expenses in institutionalization, have fewer hospital readmissions, and reduce home health benefit utilization.

Furthermore, addressing caregiving’s financial impact could stimulate communities’ economic growth. For instance, more protections for working caregivers could limit income disruptions and foster economic security. When households are more economically secure, they have more money for basic needs such as healthy food and healthcare.

Economic security also saves caregivers money for retirement and future care needs. Not only does this reduce the risk of caregiver burden, but it also eases dependency on public assistance programs, which may appeal to some policymakers.

Lastly, households with expendable income are more willing to purchase nonessential goods and services. An increase in consumer spending and purchase power are key drivers of economic growth on the local and national levels.

Ultimately, connecting family caregivers to the help they need leads to better care at lower costs. In a growing volume of research about this subject, experts suggest similar solutions for stakeholders with the power to influence and implement policies that better support informal caregivers and lower caregiver burden.

How Healthcare Systems Can Ease Caregiver Burden

The healthcare industry owes it to family caregivers to find ways to protect and support them. Health systems can start by providing caregivers with guidance and resources. Doing so is the first step toward a more comprehensive, remedial shift in how the healthcare industry recognizes and supports caregivers and care recipients.

Physicians must take time to understand their patients and their responsibilities fully. As researchers in a 2022 article stated, doing so “requires talking about caregiving.” But as AARP and NAC found, only 29% of caregivers’ clinicians asked about their needs, while 13% were asked what the caregiver needed to care for themselves.

Clinicians must also assess the needs of informal family caregivers, which can be done by treating caregiving activities like other social determinants of health. Routine assessments can make it easier to gauge the impact of caregivers’ role on their health and monitor caregiver burden over time.

Secondly, health systems must integrate caregivers into the care recipients’ care plan. Whether intentionally or not, health systems often exclude family caregivers from discussions. A caregiver may struggle to attend outpatient appointments during the workweek due to their job, school, or children.

In hospitals, inpatient teams are often unavailable after-hours when most family caregivers are. Utilizing video calls, telehealth, and other communication tools could help keep family caregivers in more discussions about their loved one’s care. By having family caregivers in more conversations and a better understanding their needs, health systems can provide more relevant support.

Third, health systems should improve access to health information. One strategy is the creation of user-friendly online portals. These platforms can facilitate communication between patients, clinicians, and caregivers while maintaining patient privacy and complying with HIPAA requirements.

Many caregivers take on care coordination alone, which can be overwhelming for those unfamiliar with the health system. So naturally, people in this situation are far more likely to experience caregiver burden. However, an online platform could feature guidance on transportation reimbursement, where to find support groups, training programs, and respite care. These would go a long way to empower caregivers with a better understanding of care plans and the knowledge to communicate effectively with physicians.

How Health Insurance Providers Can Address Caregiver Burden

Several obstacles related to the insurance industry hinder health systems from acting on policies that could minimize the occurrence of caregiver burden. For example, payment rules can discourage providers from communicating with caregivers. These restrictions also leave room for misinterpretations of privacy regulations, affecting communication between caregivers, older adults, and clinicians.

Specifically, Medicaid and Medicare plans can support family caregivers and reduce caregiver burden by outsourcing assistance to third-party partners with in-depth caregiver expertise. Insurers already utilize a multichannel approach to reach seniors and help them find the right health plan. However, they don’t always have the means to assess members’ needs after enrollment. This can make it challenging to meet members’ needs on an ongoing basis.

To better understand what seniors want most from their health plans, more Medicare providers are collaborating with partners such as MeetCaregivers. Through these partnerships, caregivers act as health plans’ eyes and ears in the members’ homes, collecting information and passing it to insurers. With this data, health plans can identify which homecare services seniors want most and design plans to meet the demand.

Additionally, the data provided through these partnerships would allow health plans to scale operations on a national level quickly. It would also allow them to merge high-touch services with technology tools to deliver long-term care and minimize caregiver burden.

How Researchers Can Address Caregiver Burden

Family caregivers are highly diverse. As a result, different groups face distinct challenges in meeting their needs. This diversity requires context-specific solutions rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. For instance, many caregivers experience financial strain. But the specific sources of stress can vary depending on the care recipient’s health, demographic factors, and social determinants of health for both caregiver and care recipient.

Of course, finding solutions for these subgroups requires a deep understanding of each. Yet, a 2016 report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) stated that research on specific caregiver groups (specifically BIPOC and other marginalized groups) is limited. Naturally, this lack of information makes it difficult to develop unique and accessible interventions for a diverse group.

NASEM researchers also found that, like other social determinants of health, a connection exists between racial/ethnic/sexual identity and health disparities. Therefore, as caregiver burden becomes a more significant public health concern, researchers must take steps to account for gender, race, ethnicity, economic status, and other social determinants as contributors to health disparities.

In addition to BIPOC caregivers, researchers should also examine caregivers who support older adults with cancer, depression, and other age-related diseases. These initiatives would increase the recognition of caregivers in the health system as crucial partners and vulnerable populations.

Are You Experiencing Caregiver Burden?

MeetCaregivers Can Help.

Most older adults wish to age in their homes, but many lack the resources to do so safely, comfortably, and with dignity. Giving caregivers the proper support will reduce the risk of caregiver burden, allowing more seniors to remain at home rather than move to a facility.

Our solutions minimize caregiver burden by empowering family caregivers with practical homecare resources, education, access to health providers, and technology such as our:

- Care Matching algorithm, which improves matches between seniors and caregivers, reducing caregiver turnover by 80% and increasing satisfaction rates among caregivers, seniors, and families to 90%.

- Family Care Portal, which lets caregivers, families, seniors, health providers, and carriers easily connect and track care plans, tasks, ADLs, medications, and health data from one app.

- Homecare marketplace, which provides additional goods to support seniors at home, such as incontinence, mobility, and accessibility products.

We’re here to help. To learn more, call 1 (888) 541-1136 or, find a caregiver today.

For more resources and information about caregiver burden and aging in place, visit our Blog.

- Boersma, P., Black, L. I., & Ward, B. W. (2020). Prevalence of Multiple Chronic Conditions Among US Adults, 2018. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200130

- Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division. (2016). Family Caregivers’ Interactions with Health Care and Long-Term Services and Supports. In R. Schulz & J. Eden (Eds.), Families Caring for an Aging America (pp. 211–252). essay, The National Academies Press. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396396/.

- Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division. (2016). Economic Impact of Family Caregiving. In R. Schulz & J. Eden (Eds.), Families Caring for an Aging America (pp. 123–150). essay, The National Academies Press. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396402/

- Heath, S. (2020, May 4). Chronic Care Must Account for SDOH Needs, Family Caregivers. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://patientengagementhit.com/news/chronic-care-must-account-for-sdoh-needs-family-caregivers

- Horner-Johnson, W., Dobbertin, K., Kulkarni-Rajasekhara, S., Beilstein-Wedel, E., Andresen, E. M. (2015). Food Insecurity, Hunger, and Obesity Among Informal Caregivers. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12(E170) https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150129

- Leykum, L. K., Penney, L. S., Dang, S., Trivedi, R. B., Noël, P. H., Pugh, J. A., Shepherd-Banigan, M. E., Pugh, M. J., Rupper, R., Finley, E., Parish-Johnson, J., Delgado, R., Peacock, K., Kalvesmaki, A., Van Houtven, C. H. (2022) Recommendations to improve health outcomes through recognizing and supporting caregivers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(5), 1265–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07247-w

- Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. (2019, February 1). Medicaid’s Role in Addressing Social Determinants of Health. Medicaid and Social Determinants of Health – RWJF. Retrieved September 19, 2022, from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/02/medicaid-s-role-in-addressing-social-determinants-of-health.html

- McHenry, K. (2020, February 18). Should Caregiving Be Considered a Social Determinant of Health? Should Caregiving Be Considered a Social Determinant of Health? — Role Reversals. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.rolereversalsblog.com/blog/2020/2/17/should-caregiving-be-considered-a-social-determinant-of-health

- Stillo, K. (2022, April 4). Industry Voices—Supporting caregivers: The next step in addressing social determinants of health. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/providers/industry-voices-supporting-caregivers-next-step-addressing-social-determinants-health

- Turnage, D. (2018, August 1). Turnage.Poster.SDOH.8.2018. Orlando, Florida; University of Central Florida.

White, D., DeAntonio, D., Ryan, B., Colyar, M. (2021). (rep.). The Economic Impact of Caregiving. Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/the-economic-impact-of-caregiving - Young, H. M., Bell, J. F., Whitney, R. L., Ridberg, R. A., Reed, S. C., & Vitaliano, P. P. (2020). Social Determinants of Health: Underreported Heterogeneity in Systematic Reviews of Caregiver Interventions. The Gerontologist, 60(Supplement 1). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz148