MeetCaregivers aims to solve problems facing seniors, families, and caregivers by addressing healthcare inequality and increasing access to high-quality care. Part of that includes raising awareness about social determinants of health and their impact on aging in place. This research article explores five social determinants of health that contribute to seniors’ unmet needs and hinder aging in place.

Social Determinants Of Health Impact On Seniors’ Unmet Needs

The country’s healthcare system has undergone a striking transformation as industry attention shifts to patient-focused care. This change has accelerated following the COVID-19 pandemic, which also accentuated the unmet needs of vulnerable populations – namely, older adults.

This change poses new opportunities for cooperation among healthcare groups to help meet seniors’ unmet needs. However, as the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging (n4a) expressed in its 2019 Policy Priorities report, success will only happen if social and medical institutions put partnership and collaboration first.

Cooperation between these groups has grown in light of the pandemic. Furthermore, rising healthcare costs have prompted some in the healthcare space to re-examine how social determinants of health impact seniors and the US healthcare system.

Understanding the factors that influence our everyday lives (whether we realize it or not) stands to benefit everyone – particularly family caregivers providing care for aging loved ones.

What Are Social Determinants Of Health?

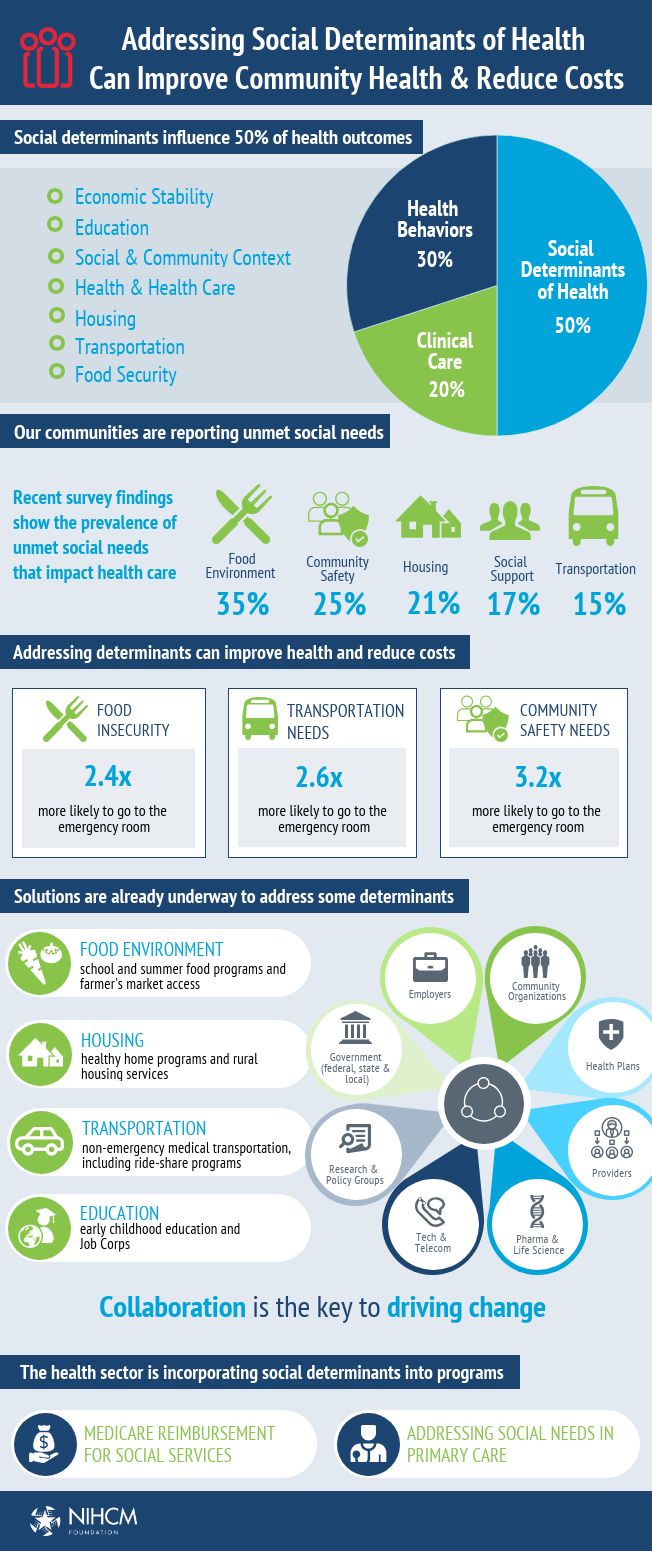

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines social determinants of health as “conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health and quality-of life-risks and outcomes.” These factors, plus genetics, lifestyle, and healthcare guidelines, play a part in the population’s general health and wellbeing.

Social determinants of health include access to necessities such as:

- Housing

- Nutrition

- Education

- Social support

- Healthcare services

Sadly, many seniors lack adequate access to housing, nutrition, financial aid, transportation, and social support. These unmet needs are one culprit behind growing healthcare costs, particularly for older adults with chronic conditions or disabilities. But healthcare costs aren’t the only area this problem affects. In a 2018 report, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) and Altarum found that health disparities contribute to:

- $135 billion in economic losses,

- $93 billion in extra healthcare costs, and

- $42 billion in lost productivity.

Addressing these factors is vital to promoting sustainable, long-lasting health outcomes for the whole population. Additionally, doing so eases federal, state, and local economies’ financial burdens and leaves more resources for programs to help meet peoples’ unmet needs.

How Unmet Needs Impact Aging In Place

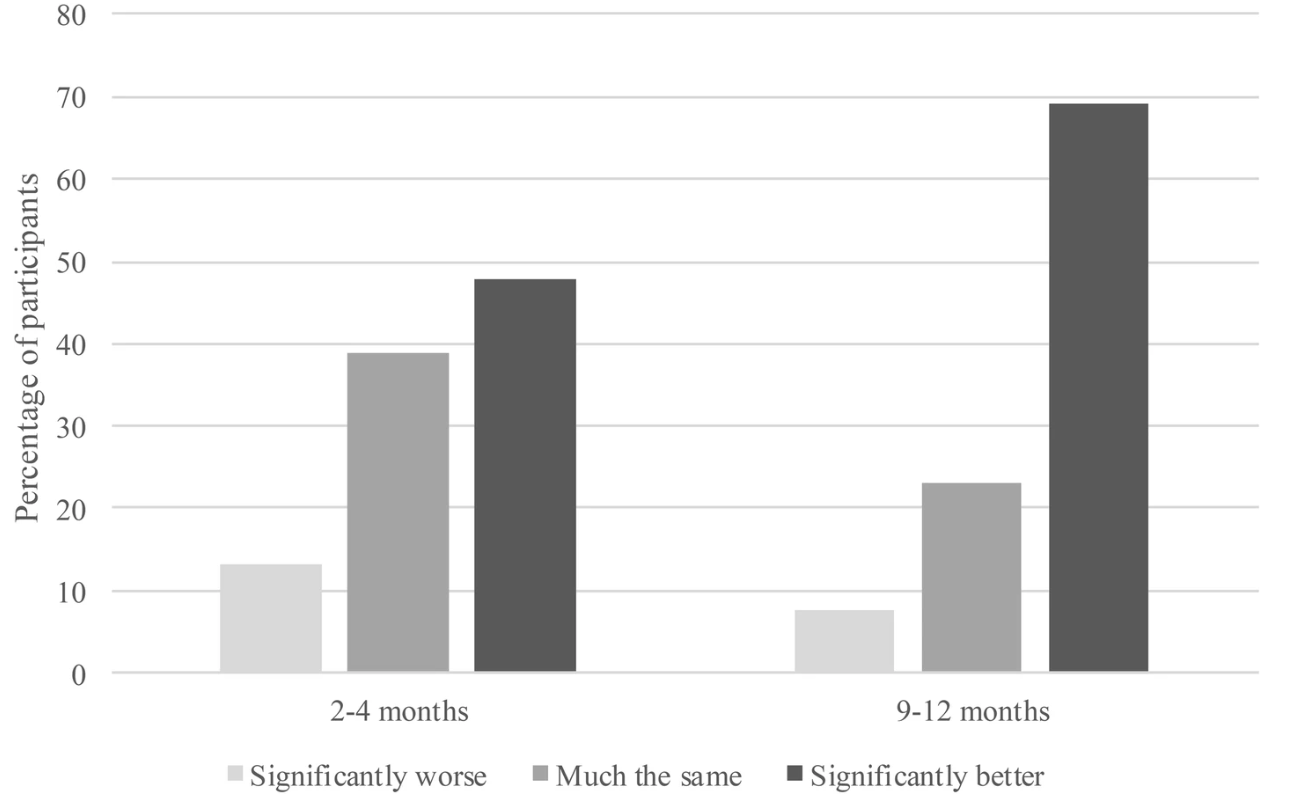

Most older adults wish to age in place, yet, a 2020 research report found that only 33% of surveyed seniors believed they could realistically age in place. According to researchers, the main barriers preventing seniors from aging in place included:

- Social barriers

- Care accessibility

- Perceived care quality

Additionally, those surveyed noted their biggest concerns included:

- Food security (50%)

- Health literacy (47%)

- Housing security (46%)

Social determinants of health such as those above can lower older adults’ likelihood of aging at home by 7%. In-home care services can help, but a fragmented care system hinders many seniors from seeking it. As a result, caregiving responsibilities often fall on other family members, of whom 34% care for a chronically ill loved one, and 41% are younger than 38.

A stronger, more cohesive care provider network is essential for both seniors and family caregivers. Not only will more people have resources age in place comfortably and safely, but it would relieve many burdens for family caregivers.

Housing

Aging in place is attributed to better health outcomes, wellbeing, and quality of life. So it’s understandable why 90% of older adults want to age in place rather than move into a nursing care facility. However, access to safe and affordable housing restricts many seniors living on low- or fixed incomes from aging in place.

For many older Americans, housing is one of the most significant monthly expenses. In 2016, housing accounted for nearly 50% of 4.9 million older adults’ incomes, while more than 1 million seniors lived in low-income housing, accounting for 30% of public housing residents.

Access to affordable housing is essential for meeting seniors’ unmet needs, improving health outcomes, and easing the burden on health systems. Unfortunately, high housing costs leave cost-burdened seniors little room in their budgets for essentials like food, utilities, and medical bills.

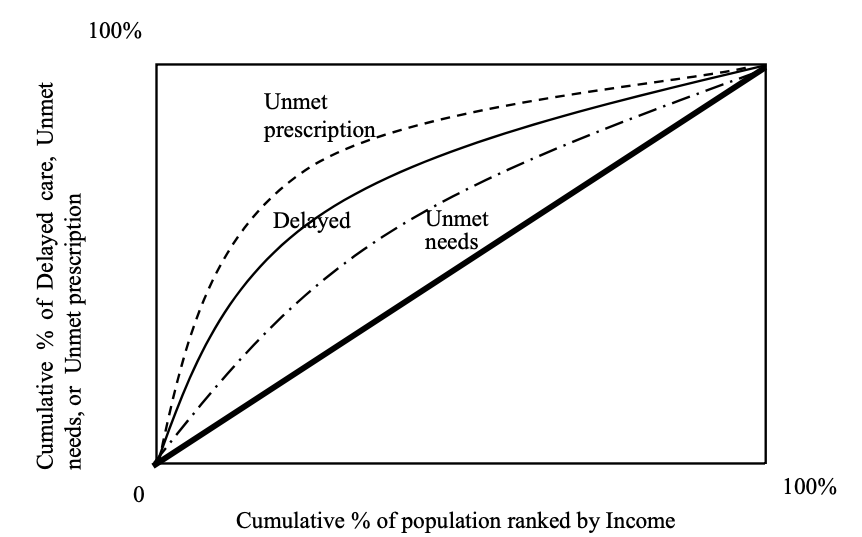

A growing body of research highlights the strong connection between income and health service utilization. For example, a 2008 study published in The Journal of Community Practice and a 2017 article published in The Gerontologist noted that low- and even middle-income individuals are less likely to seek medical care and more likely to experience poorer health outcomes.

Nutrition

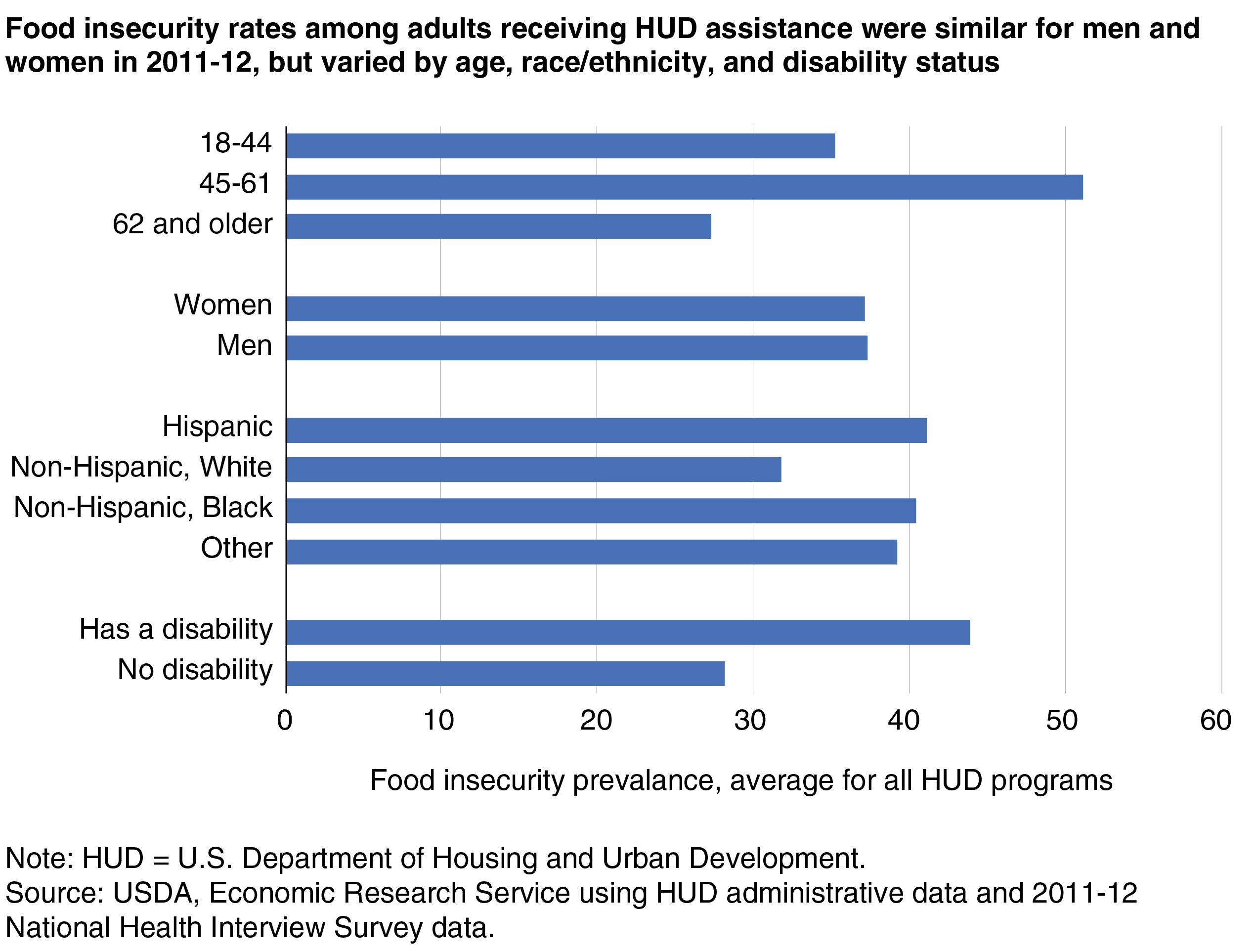

According to a Michigan State University study, food insecurity affects 8.9% of seniors who live alone, while 3.4% face “very low food security.” In addition, researchers cited a 2015 report from the Food Research Action Center, which stated:

“Research shows that certain groups of older adults are at greater risk for food insecurity than others. Food-insecurity rates tend to be higher among older adults who are low income, less educated, Black, Hispanic, separated or divorced, never married, renters, residing in the South (e.g., Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Texas, Alabama), unemployed, living alone, living with a disability, living with grandchildren, or ‘younger’ older adults (i.e., those 50 to 59 years of age).”

Access to healthy food that meets older adults’ nutritional needs is a critical social determinant of health that directly affects their quality of life. A nutritious, balanced diet plays a prominent role in the prevention of chronic conditions such as:

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- Hypertension

- Cardiovascular disease

Unfortunately, the conditions disproportionally affect people who can’t afford healthy ingredients or live in food deserts. Transportation, income, and location are the biggest obstacles for many food-scarce seniors and reveal how social determinants of health entwine and exasperate considerable disparities.

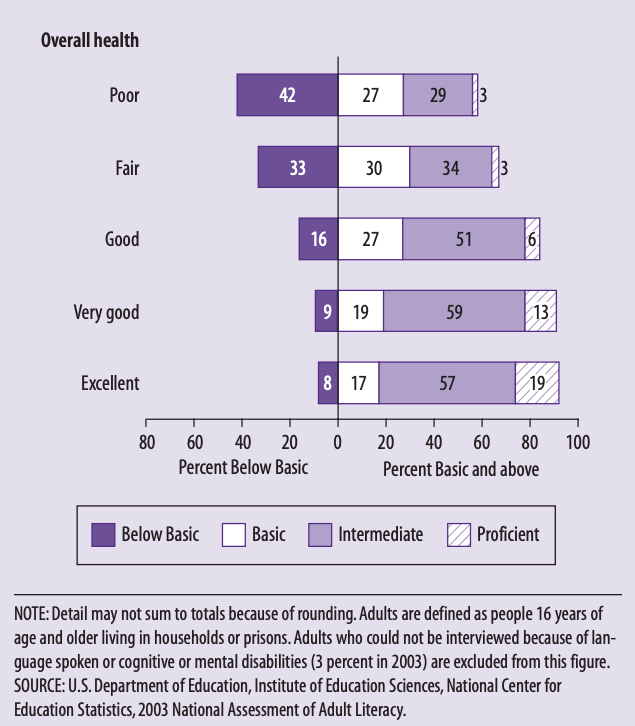

Education & Health Literacy

Health literacy is “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” and is the basis of health and wellbeing. Yet a 2003 study from the US Department of Education found that health literacy among adults 65 and older was lower (on average) versus younger generations – which is likely still the case nearly 20 years later.

Unfortunately, individuals with lower health literacy lack the understanding or resources to make informed health decisions, worsening other unmet needs. Consequently, they often experience challenges such as:

- Difficulty following treatment programs or a medication routine.

- Higher pain and diminished physical abilities (which can hinder the completion of daily activities).

- Repeat hospitalizations or emergency room visits.

- Higher medical costs as a result of higher rates of emergency service utilization.

These obstacles are more likely to impact older adults than other age groups, so to support literacy among this group, experts recommend the implementation of systematic changes such as:

- Streamlining communication between patients and physicians.

- Minimizing miscommunications by confirming patients’ understanding.

- Helping seniors navigate the health care system.

- Supporting older adults trying to improve their health.

Social Support

Healthy relationships and strong social networks support physical and mental health and affect behavioral and psychological pathways that can improve health outcomes. Social support can also indirectly guard against adverse health risks, such as easing emotional anxiety.

Given the importance of a positive social support system on health, social isolation can lead to poorer health outcomes and even premature death. Loneliness and isolation are particularly problematic for seniors, whose social networks often diminish with age.

Isolation and loneliness in seniors are linked to numerous somatic issues, making it one of the health care system’s biggest challenges. If left unchecked, these states can lead to higher rates of:

- Falls

- Heart disease

- Cognitive decline

- Depression and other mental health problems

According to a 2017 AARP report, 14% of seniors suffered from isolation yet constituted $6.7 billion in additional federal spending. The pandemic only worsened this problem, with a 2020 survey finding that 61% of older adults over 50 considered themselves socially isolated.

The lack of preventative measures provided by federal and state governments is particularly detrimental for seniors in rural communities, where unmet needs such as a lack of transportation only amplify isolation. Furthermore, social supports that support seniors’ health significantly differ and sometimes call for cooperation among multiple sectors (education, housing, public health) to promote community and increase individual wellbeing.

Healthcare Access

Limited access to health services is another factor that contributes to seniors’ unmet needs and poorer health outcomes. This problem is partially driven by economic insecurity, which affects more than 15 million seniors in the US. Within this group, 50% receive most of their income from Social Security.

A 2008 report found that “compared with affluent adults, poor adults are nearly five times as likely to report being in poor or only fair health.” Whether due to cost, a limited provider network, or another reason, under-, and uninsured adults are less likely to seek the treatment they need when they need it. As a result, health expenses for previously uninsured seniors are 51% higher than for the previously insured.

Policies like the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have helped curb rising healthcare costs for older adults, increasing the availability of health services for under- or uninsured older adults.

These policies are also crucial for federal spending, which surpassed $702 billion, or nearly 15% of its total budget, on Medicare in 2017. And in 2019, one out of six older adults (roughly 60 million) received coverage. But as the number of Medicare-eligible older adults grows, so will costs, with some experts projecting spending to exceed $1 trillion by 2026.

The rate of aging adults in the US isn’t the only contributing factor to Medicare increases. To some degree, social determinants of health contributing to seniors’ unmet needs are also responsible. For example, Medicare is supposed to help offset acute in-patient care costs. Yet it has historically denied coverage for many preventative measures that could prevent the need for in-patient care in the first place. And while policymakers expanded Medicare supplemental benefits to support independence and health, including home-based care, many still receive limited assistance.

Furthermore, some state CMS agencies have considered revoking or shrinking provisions such as non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) services. This move would also increase costs, as coverage for services such as NEMT is vital to promoting seniors’ wellbeing and independence. According to a 2018 study from the Medical Transportation Access Coalition (MTAC), NEMT “saves Medicaid, and thereby taxpayers, more than $40 million per month for every 30,000 beneficiaries receiving treatment for one of three conditions covered in the study.”

For the nearly 66% of Medicare recipients with multiple chronic conditions, transportation assistance helps them attend routine health appointments and receive needed care, preventing minor issues from becoming costly expenses. Removing benefits like these hinders seniors’ access to preventative care, further increasing costs for Medicaid recipients, payers, and taxpayers.

Ageism Contributes To Seniors' Unmet Needs

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines ageism as “the stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination directed towards people on the basis of their age.” Ageism occurs in institutional settings, in day-to-day interactions, or even within individuals. In its 2021 Global Report on Ageism, the WHO noted the pandemic highlighted ageism in various areas, such as:

- Disparities in healthcare access

- Media stereotypes that alienate generations

- Insufficient measures to protect the elderly living in care homes

Ageism often goes overlooked as a social determinant of health, despite the known detriments for older adults, such as:

- Shorter lifespans

- Faster rates of cognitive decline

- Diminished physical and mental health

- Higher risk of social isolation and loneliness

- Slower recovery following an illness or disability

- Less access to employment, education, and medical care

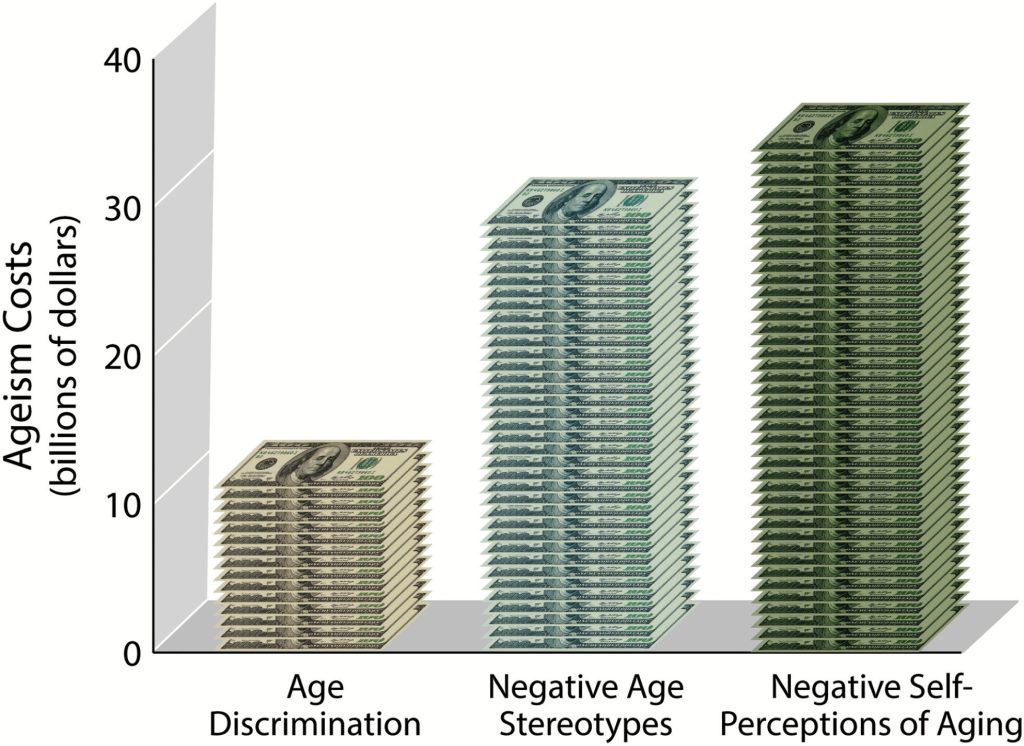

As one study found, ageism costs older adults 60 and over an additional $63 billion (or $1 in every $7) in health care every year. But ageism doesn’t just impact individuals; the consequences extend to communities, states, economies, and healthcare systems. The far-reaching ripple effects highlight the importance of eliminating the factors that help ageism persist. But ageism’s multifaceted nature also makes the issue more challenging to combat. In response, the WHO offers three methods to stop ageism:

- Regularly engage in positive, multigenerational activities.

- Confront age-related discrimination and disparity with policies and laws to defend human rights.

- Change misconceptions, accurate information, and contradicting stereotypes by removing barriers at every education level.

By implementing the strategies above, policymakers and leaders at every level help reduce ageism while addressing a critical social detriment of health and fulfilling seniors’ unmet needs.

MeetCaregivers Helps Meet Seniors' Unmet Needs

Most seniors want to stay in their homes but don’t always have the resources to do so. We support aging in place by reducing factors that contribute to seniors’ unmet needs, such as:

- Supporting independence

- Managing chronic conditions

- Reducing loneliness and isolation

- Increasing access to preventative care

Our solutions also empower family caregivers with practical in-home care resources, including education, home health providers, and technology tools such as:

- Our Care Matching algorithm improves matches between seniors and caregivers, reducing caregiver turnover by 80% and increasing satisfaction rates among caregivers, seniors, and families to 90%.

- The Family Care Portal lets caregivers, families, seniors, health providers, and carriers easily connect and track care plans, tasks, ADLs, medications, and health data from one app.

- Our homecare marketplace provides additional goods to support seniors at home, such as incontinence, mobility, and accessibility products.

To learn how we can help, call 1 (888) 541-1136 or email info@meetcaregivers.com to book a meeting with a care coordinator. You can also visit Find A Caregiver to find help today.

For more resources and information about caregiving and aging in place, visit our Blog.

Sources

- AARP Foundation, & United Health Foundation. (2020, October 6). The Pandemic Effect: A Social Isolation Report. Connect2Affect.org. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://manuals.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/ALTSA/stakeholders/documents/SCOA/The-Pandemic-Effect-A-Social-Isolation-Report-AARP-Foundation.pdf

- Balaswamy, S., & Dabelko, H. I. (2002). Using a Stakeholder Participatory Model in a Community-Wide Service Needs Assessment of Elderly Residents. Journal of Community Practice, 10(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/j125v10n01_04

- Braveman, P., & Egerter, S. (2008). (rep.). RWJF.org. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from http://www.commissiononhealth.org/PDF/ObstaclesToHealth-Report.pdf.

- Cameron, K., & Vafiadis, D. K. (n.d.). Social Determinants of Health: 100 Million Healthier Lives. GIAging.org. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.giaging.org/issues/social-determinants-of-health/

- Chase, A. (2015, December 31). Combating Food Insecurity: Tools For Helping Older Adults Access SNAP AARP Foundation Food Research and Action Center (FRAC). Cupdf.com. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://cupdf.com/document/combating-food-insecurity-tools-for-helping-older-adults-access-snap-aarp.html

- DeAngelo, K., & Haskell, S. (2022, January 21). Are we Leaving our Seniors Food Insecure and Deserted? Canr.MSU.edu. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/are-we-leaving-our-seniors-food-insecure-and-deserted

- Flowers, L., Harvard University, Stanford University, AARP Public Policy Institute, Farid, M., Shoemaker, L., Bhattacharya, J., Shaw, J., Noel-Miller, C., & Houser, A. (2017, November 13). Medicare Spends More on Socially Isolated Older Adults. AARP.org. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/10/medicare-spends-more-on-socially-isolated-older-adults.pdf

- Fournier, S., & Health and Human Services Commission Office of Aging Services Coordination. (n.d.). Social Determinants of Health in Aging. HHS.Texas.gov. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/about-hhs/community-engagement/atw/atw-social-determinants-health-aging.pdf

- Fresenius Medical Care. (2020). (rep.). FMCNA.com. Fresenius Medical Care. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://fmcna.com/aging-in-place/.

- Heath, S. (2020, March 12). Social Determinants of Health Hamper Efforts to Age in Place. PatientEngagementHIT.com. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://patientengagementhit.com/news/social-determinants-of-health-hamper-efforts-to-age-in-place

- Housing as a Social Determinant of Health for Low-Income Older Adults. (2016). The Gerontologist, 56(3), 740–741. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw162.3017

- Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1745-1772; doi:10.3390/ijerph120201745

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Chang, E.-S., Kannoth, S., & Wang, S.-Y. (2018). Ageism Amplifies Cost and Prevalence of Health Conditions. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny131

- Magnan, S. (2017). Social Determinants of Health 101 for Health Care: Five Plus Five. NAM Perspectives, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.31478/201710c

- McWilliams, J. M., Meara, E., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2007). Use of Health Services by Previously Uninsured Medicare Beneficiaries. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa067712

- Meals on Wheels of Central Indiana. (2020, August 31). Social Determinants of Health & Nutrition. MealsOnWheelsIndy.org. Retrieved April 29, 2022, from https://mealsonwheelsindy.org/social-determinants-of-health-nutrition/

- Medical Transportation Access Coalition. (2018, August 1). Study Reveals Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT) is Extremely Cost-Effective and Life-Saving to Medicaid Program. MTACCoalition.org. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://mtaccoalition.org/study-reveals-non-emergency-medical-transportation-nemt-is-extremely-cost-effective-and-life-saving-to-medicaid-program/.

- Mikton, C., de la Fuente-Núñez, V., Officer, A., & Krug, E. (2021). Ageism: A social determinant of health that has come of age. The Lancet, 397(10282), 1333–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00524-9

- Molinsky, J., & Airgood-Obrycki, W. (2018, September 21). Older Adults Increasingly Face Housing Affordability Challenges. JHCS.Harvard.edu. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/older-adults-increasingly-face-housing-affordability-challenges

- NIHCM Foundation, May 07, 2020. The Current State of Food Insecurity in America. NIHCM Foundation. https://nihcm.org/publications/addressing-social-determinants-of-health-can-improve-community-health-reduce-costs

- n4a. (2019). Improve Health by Addressing the Social Determinants. USAging.org. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www.usaging.org/files/Improve%20Health%20by%20Addressing%20the%20Social%20Determinants.pdf

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Social Determinants of Health. Health.gov. Retrieved May 9, 2022, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Park, S., Kim, B., & Kwon, E. (2017). The Role of Senior Housing in Hospitalizations Among Vulnerable Older Adults With Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Longitudinal Perspective. The Gerontologist, 58(5), 932–941. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx046

- Parkman, K. (2021, April 12). 2021 Elderly Poverty Statistics: How Economic Problems Affect Seniors. ConsumerAffairs.com. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.consumeraffairs.com/finance/elderly-poverty-statistics.html Updated February 17, 2022

- Turner, A. (2018, April 24). The Business Case For Racial Equity: A Strategy For Growth. Altarum.org. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/WKKellogg_Business-Case-Racial-Equity_National-Report_2018.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Health Literacy. HealthyPeople.gov. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/health-literacy

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (n.d.). What Is Health Literacy? CDC.gov. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html Page last reviewed: February 2, 2022

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Social Cohesion. HealthyPeople.org. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/social-cohesion

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Social Determinants. HealthyPeople.gov. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Social-Determinants